August

is a strange month to be sitting in a locked room. Curtains closed to

keep the blaze of sunshine from the obscuring the computer's glare.

Half-starving, shivering in trenches (imaginatively) whist outside

summer burgeons and allotments fatten. But I was excited to be

leading my first digital writing residence and for seven days, it

felt as if the flickering screen was my patch of sky. When I wasn't

googling research sites, jotting exercises or tweeting about it, I

was waiting for the cheep of e-borne post. The residency was

commissioned by WritingEast Midlands

in conjunction with a national body responsible for organising

suitable cultural commemorations of WW1. Someone in 14-18-NOW

had the idea of a unique 'memorial

of words'

from today's generation and nationwide, schoolchildren, pensioners,

squaddies and civilians, writers and other artists, were drafted to

pen a Letter tothe Unknown Soldier

of Paddington Station.

August

is a strange month to be sitting in a locked room. Curtains closed to

keep the blaze of sunshine from the obscuring the computer's glare.

Half-starving, shivering in trenches (imaginatively) whist outside

summer burgeons and allotments fatten. But I was excited to be

leading my first digital writing residence and for seven days, it

felt as if the flickering screen was my patch of sky. When I wasn't

googling research sites, jotting exercises or tweeting about it, I

was waiting for the cheep of e-borne post. The residency was

commissioned by WritingEast Midlands

in conjunction with a national body responsible for organising

suitable cultural commemorations of WW1. Someone in 14-18-NOW

had the idea of a unique 'memorial

of words'

from today's generation and nationwide, schoolchildren, pensioners,

squaddies and civilians, writers and other artists, were drafted to

pen a Letter tothe Unknown Soldier

of Paddington Station.

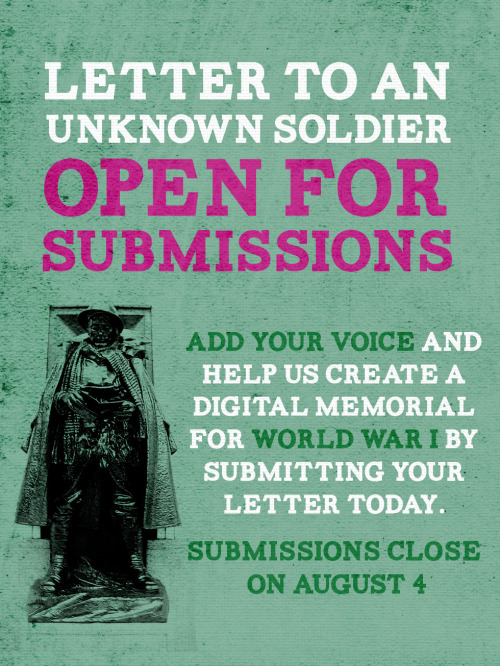

He's

an approachable soul. When you get above the height of the marble

plinth, he looks like an ordinary young man from your street. In the

bulky uniform of a WW1 Private, he wears a voluminous greatcoat and a

non-regulation knitted scarf. He is reading a letter and the

14-18-NOW project invited us to write that Letter

From Home.

But we had seven days to play with so I devised exercises each day on

themes around the Paddington statue - or 'our

friend Tommy'

as we came to call him. Moving through reflections on the STATION,

BOOTS, LETTER, HELMET, SCARF, GREATCOAT and MEMORIAL, we edged

further and further into his nightmarish world of troop trains,

trenches, shell-holes. It was impossible not to be disturbed,

horrified and deeply saddened at the industrial slaughter and daily

privations these Tommies suffered.

For

me, the experience was lightened by the beautiful writing and

enthusiastic engagement of the week's work-shoppers. As it turned

out, these included some experienced writers, already knowledgeable

about WW1. Each day along with writing prompts and exercises, I

posted videos, images and web-links garnered from a wide range of

on-line sources. We explored the WW1 'field' postal depots and a

French cottage industry producing silk embroidered postcards on a huge scale for

soldiers to send home. We wrote about trench foot and shell-shock,

about Boy Soldiers (Britain's 250,000 underage recruits) and dawn

executions. My 'posties' delivered witty, insightful and moving

accounts of desert bombing raids, 'Munitionettes' and life on the

Home Front too. After all, this 'Total War' not only spanned the

globe but revolutionised social and gender relations as well as the

technology of killing human beings in unforeseen numbers.

A

century on, a digital writing course is probably a fitting venture

for 2014. The unpredictability of who and when was a challenge for me

but the flexibility was appealing to workshoppers. With open access

24/7, they could pick through which of the resources and exercises

they wanted to tackle and post when they were ready. An attempt at

'live

workshops' faltered

– it proved better for people to work at their own pace. But they

could share the 'texts' they produced – poems, stories, dialogue

fragments – and converse with each other via forumthreads.

I critiqued each piece posted but also found their feedback

invaluable on my own attempts at exercises. So fruitful was this,

that subsequently I have drafted a dozen 'Unknown Soldier' poems.

An unexpected bonus.

When

we emerged blinking from this digital dug-out, it was the 4th

August. We were posting our final Letters just as the nation marked

the 100thanniversary of the War declaration.

A sobering moment. But also the culmination of a week's creativity,

exploring our own responses to war, and imaginatively re-entering

that charged landscape of the past. I am grateful to WEM for the

opportunity and to my 'posties' for their openness to writing

challenges, their willingness to venture into some dark places and

their companionship. I hope we shall see more of their WW1 writing

but you can read their Letters to 'our friend Tommy' along with

21,408 others on the 14-18-NOWUnknown Soldier website.

They will be available to read there until 2018 when they will be

stored permanently in the British

Library's

digital archive. At which point, our voices and letters will merge into that polyphonic postbag that is our own 'history'.